Introduction

Just recently, the United States joined Israel’s mission of dismantling Iran’s nuclear capabilities by conducting airstrikes that targeted three of Iran’s key nuclear facilities at Fordo, Natanz, and Esfahan. This is significant in terms of American-Iranian relations because it is the largest escalation between the two nations since the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, in 2020. With the American decision to take kinetic action against Iran’s nuclear facilities, it seems like tension between the bitter rivals is at an all-time high. But to truly understand how we arrived at this moment, we have to look beyond the headlines and into the past.

Long ago, early Americans saw Persia as a land of ancient grandeur with regal beauty and wisdom. In turn, many Persians admired America’s spirit of independence and its promise of freedom and liberty. As history would have it, what began as a mutual fascination gradually curdled into mistrust, then hardened into resentment. In the eyes of both nations, the other is guilty of a long list of transgressions that are difficult to overcome. For the past four decades, the Americans and Iranians haven’t been able to agree on just about anything. To understand where the diplomatic bridge was burned between our two nations, we must examine when the fire was first lit.

The 1953 Coup

The relationship between the West and Iran began to fracture after World War 2, when the Allied powers (specifically the British and Soviets) ended their occupation of Iran during the war and installed the younger and less capable son of the former shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, as the new shah. Reza Pahlavi was very unpopular among the population and was perceived as a puppet of the British. There was growing frustration across the country, not just with the Shah’s authoritarian style, but with how much control foreign interests had over Iran’s economy, particularly its oil. In 1951, that discontent came to a head when Iran’s parliament voted to sideline the Shah’s authority and appoint Mohammad Mossadegh, a respected lawyer and secular nationalist, as Prime Minister.1

Mossadegh quickly became a symbol of Iranian pride and nationalism. One of his biggest goals that made him popular, particularly among the youth, was taking back control of Iran’s oil industry. At the time, British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (which later became BP) was essentially running the show. The British were raking in massive profits from Iranian oil, while Iran got only a tiny cut and had no real oversight or transparency into how the business was run.2 Most Iranians knew their country was being exploited for its resources, and wanted it to come to an end. They wanted Iran to be able to benefit from and control their most prized import, oil, and saw it as an opportunity to create jobs for Iranians and help lift the nation out of poverty and exploitation.

To achieve this goal, Mossadegh decided to nationalize Iran’s oil industry. This move was hugely popular in Iran but set off alarm bells in London, and Britain responded by imposing an embargo and blocking Iran’s oil exports, hoping to force Mossadegh to back down. When that didn’t work, British intelligence, M16, worked with the CIA to organize a coup to overthrow Mossadegh and replace him with a more Western-friendly leader. In 1953, Mossadegh was overthrown, and the Shah was brought back to full power, this time with even more backing from the West. After the 1953 coup that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, he was replaced by Fazlollah Zahedi, a retired general who had opposed Mossadegh and was favored by both the British and the CIA.3

Zahedi was installed as Prime Minister with the full backing of the Shah, who had fled Iran during the coup attempt but returned shortly after Mossadegh was removed. While Zahedi held the title of Prime Minister, real power quickly shifted back to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who gradually consolidated control and ruled Iran as an absolute monarch for the next 25 years with strong support from the United States. Iran was now under authoritarian rule by a shah who was largely seen as illegitimate and more aligned with Western interests rather than the interests of the Iranian people. This perceived violation of Iranian sovereignty at the hands of the Americans and British against the Iranian people left feelings of distrust and betrayal among the population, but these scars would grow much deeper with what was to follow next: the SAVAK.

The SAVAK

After the US and Great Britain installed Reza Pahlavi as Shah, they had to find ways to mitigate opposition and resistance to his authority. One of the ways that they decided to do this was the formation of the SAVAK, which was Iran’s secret police and intelligence agency under the Shah’s regime. Established in 1957 with assistance from the CIA and Israel’s Mossad, its main purpose was to suppress political dissent and protect the Shah’s regime. SAVAK quickly became one of the most feared organizations in Iran, employing tens of thousands of agents and informants who infiltrated nearly every aspect of Iranian life, from universities and mosques to the military and press. SAVAK became a shadow over the Iranian public and served as a warning that troublemakers for the Shah would be met with swift and brutal punishment.4

Reports of widespread human rights abuses by SAVAK began surfacing in the 1960s and 70s. These included surveillance, arbitrary arrests, torture, and even executions of political prisoners. For many Iranians, SAVAK became the embodiment of tyranny and oppression, which angered a society that had American values advertised to them as the opposite of those things. SAVAK was trained by both the Israeli Mossad and the CIA, and its direct association with American intelligence only deepened resentment toward the U.S. Western human rights groups and journalists began exposing SAVAK's actions, which undermined the Shah’s image abroad and turned the Iranian public further against both his regime and its foreign backers.

SAVAK's role in fueling opposition to the Shah cannot be overstated. Its brutality was a key factor in unifying a broad coalition of anti-Shah groups, including secular intellectuals, Marxists, students, and Islamists. When the 1979 Iranian Revolution unfolded, which I will discuss next, it was driven not only by opposition to the monarchy but also by a deep-seated anger toward the U.S., which was seen as complicit in decades of repression. The SAVAK ushered in an era of torture and fear in Iran and was viewed as the iron hand that was used to impose a perceived cultural imperialism on the population.

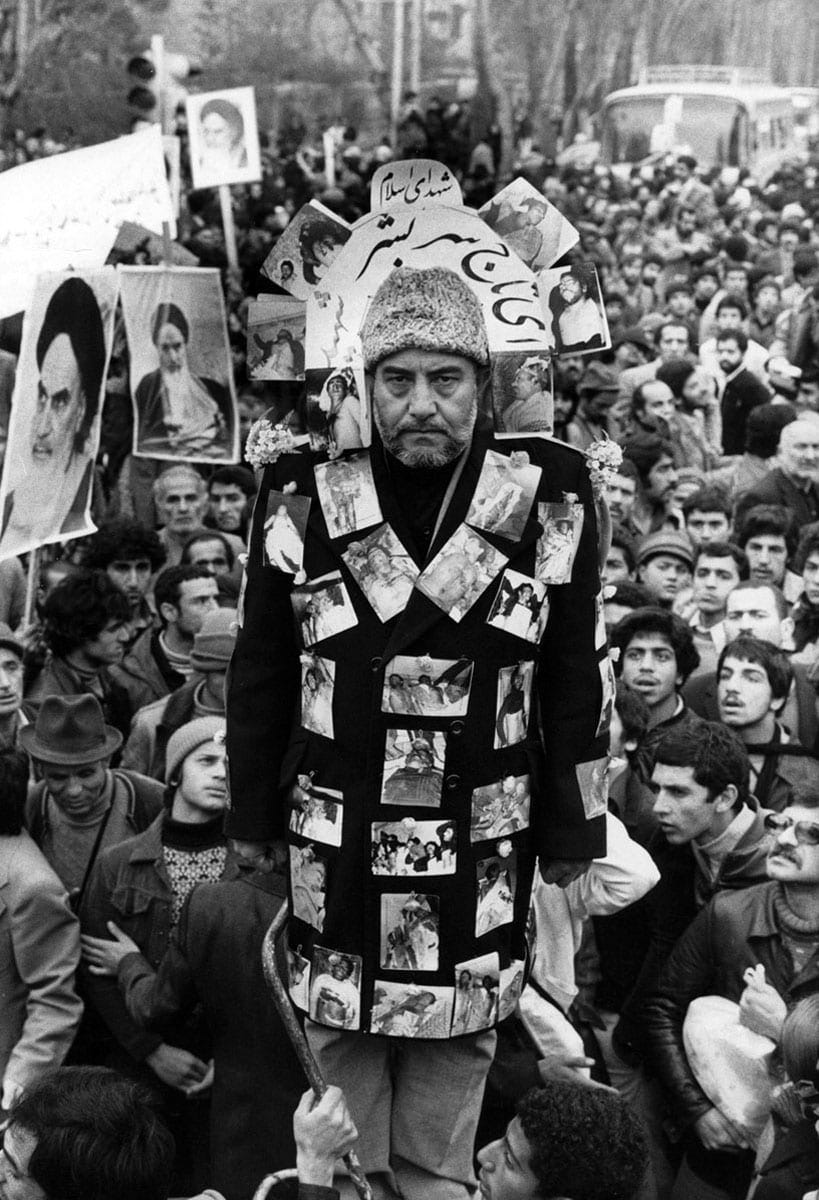

The 1979 Revolution

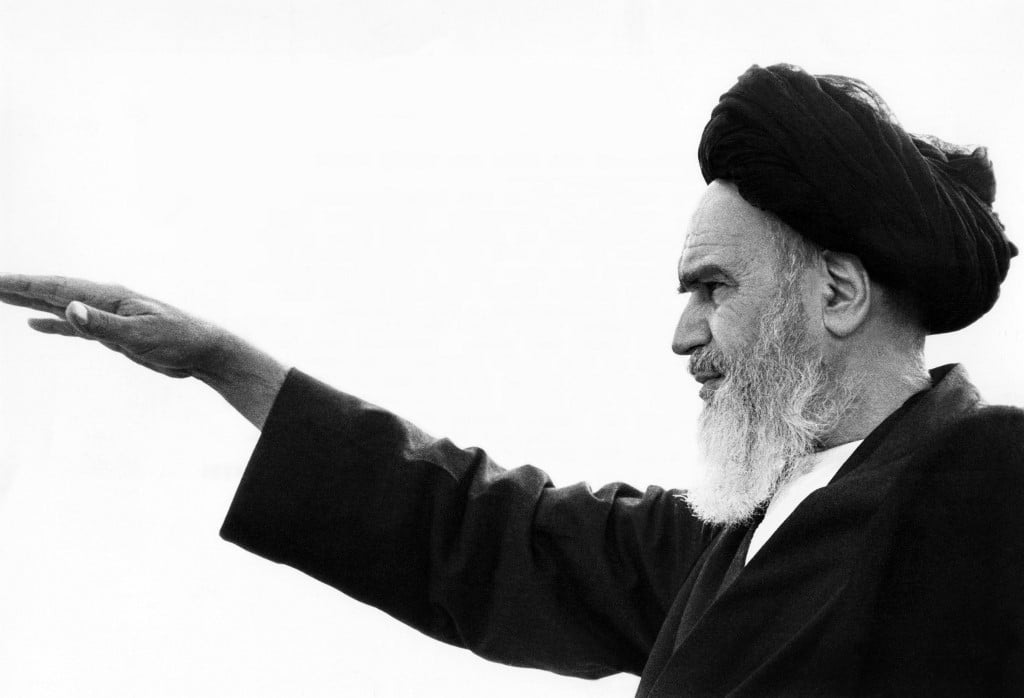

One of the Shah’s most significant modernization efforts was the White Revolution, a series of reforms aimed at rapidly transforming Iran’s economy and society. It included land reform (breaking up large feudal estates and redistributing them to peasants), the nationalization of forests and pastures, the expansion of women’s rights (including the right to vote and the elimination of Islamic clothing restrictions), and increased government investment in education and healthcare.5 While intended to modernize and Westernize rural Iran, the reforms often disrupted traditional power structures and angered both the clergy and landowners. Among those who were angered by the Shah’s attempts to westernize Iran was the exiled cleric Ayatollah Khomeini. The Ayatollah had a passionate and large following within Iran for his Islamic teachings and his writings about his ambitions to implement Sharia Law as a form of governance. Khomeini was deeply interested in politics and had a vision for Iran not to be ruled by the monarchy of the Shah, but by Islamic religious teachers who formulated and enforced the rule of law as prescribed by the Quran.6

After years of rising public mistrust of Reza Pahlavi and mounting frustration from Iran’s traditional Shiite Muslim population, the Shah was overthrown in 1979 and fled the country. Ayatollah Khomeini came out of exile to rule Iran and establish the Islamic Republic of Iran, thus ending the Persian monarchy and starting a new era in the country’s long history. The 1979 Iranian Revolution dramatically increased anti-American sentiment in Iran, transforming the relationship between the two countries and reshaping Iranian national identity around opposition to the United States.7 While resentment toward the U.S. had been building for decades, the revolution crystallized and institutionalized it, embedding anti-Americanism deeply into the ideology of the new Islamic Republic. To the now Islamic country, America earned the title of the “Great Satan” and was viewed as not only an enemy of Iran, but of Islam as well. Understanding the religious element that essentially became government doctrine for Iran during this revolution is fundamental in understanding how Iranian resentment towards America is multi-layered. Khomeini and the clerical establishment portrayed the revolution as not just a rejection of the Shah, but a rejection of Western domination and secularism. The United States, in their view, was the primary force behind both. This rhetoric helped unify the post-revolutionary regime and rally the population around a common enemy, the Americans.

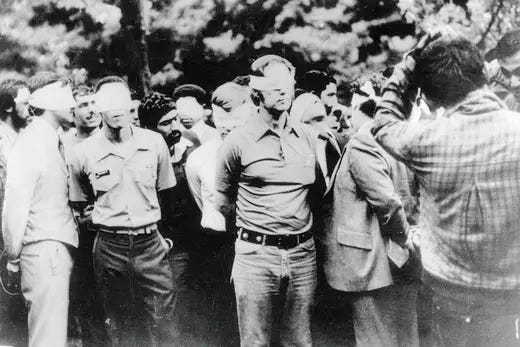

The Iranian Hostage Crisis

Perhaps the most direct and symbolic event that intensified anti-American sentiment was the 1979 U.S. Embassy hostage crisis. In November of that year, Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took 52 American diplomats and staff hostage for 444 days.8 The students claimed they feared another U.S.-backed coup (think of the 1953 coup with Mossadegh) and wanted to expose American interference in Iranian affairs. The crisis was broadcast around the world and became a defining moment in U.S.-Iran relations. Inside Iran, the hostage-takers were celebrated as heroes, and the event became a powerful symbol of defiance against Western imperialism. Back in the United States, the American public, which was largely disinterested in Iran prior, had gotten its first taste of what would become a mutual resentment between the two nations. Night after night, people watched the news, helpless and angry, as the hostages remained in captivity. It stirred a sense of national humiliation and disbelief: how could a country that many viewed as distant and underdeveloped hold the United States hostage, literally and figuratively, for over a year?

A major trigger for the embassy takeover was President Jimmy Carter’s decision to allow the exiled Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to enter the U.S. for cancer treatment. In the eyes of the Iranian people, still recovering from living under the dark shadow of the SAVAC, they felt that the Shah deserved to be held accountable for his crimes against the Iranian people. Many feared that allowing the Shah refuge in the U.S. was the first step in a possible American plot to return him to power. The revolution was still fresh, and the memory of the Shah’s rule, filled with censorship and torture, had not faded. Protesters demanded his return to Iran to stand trial for crimes against the people, with many calling for his execution.

Since the hostage crisis, formal diplomatic relations between Iran and the U.S. have been severed. Neither country has had an embassy in the other, and instead, they communicate through intermediaries like the Swiss Embassy, which represents U.S. interests in Tehran. In addition to cutting diplomatic ties, the U.S. responded with sweeping economic sanctions, which have only grown over the years and continue to affect Iran’s economy and international standing today.

Iran-Iraq War

In 1980, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Iran, largely out of fear that Iran’s Islamic Revolution might inspire a Shiite uprising against his regime. The resulting war dragged on for eight brutal years and cost the lives of nearly a million Iranians, with little, if anything, to show for it in the end. While there’s a lot that could be said about how the Iran-Iraq War shaped Iran’s approach to global politics, I want to focus on one key aspect: how this conflict further damaged Iran’s already strained relationship with the United States. During the war, the U.S. supplied Iraq with intelligence and satellite imagery to help it target Iranian troops. The U.S. government did not directly sell weapons to Iraq but helped facilitate weapon sales through other nations such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Looking back at the long and complicated history between the two countries, I have noticed that this chapter is often overlooked. But in my view, it was one of the most profoundly damaging moments. At a time when Iran was still recovering from the trauma of the revolution and the hostility of the hostage crisis, seeing the U.S. throw its weight, however indirectly, behind Saddam Hussein only confirmed the worst fears many Iranians had about American intentions.

While Iran was greatly enraged by American assistance to Iraq during the war, it is not merely the assistance alone that seared this perceived American betrayal into the Iranian memory. Iran to this day has not forgiven the Americans for turning a blind eye to Saddam’s use of chemical weapons against the Iranians (both on military and civilians) during the war, which included mustard gas and nerve agents.9 In the view of the Iranians, this symbolized a major contradiction in America’s values of defending human rights and individual freedom. Iranians believed the U.S. was encouraging Saddam to keep the war going to weaken Iran, bleed its economy, and destabilize its new revolutionary government. The U.S.'s failure to condemn Iraq's use of chemical weapons only reinforced this perception of American duplicity. This perceived double standard was demonstrated again during the Iran-Contra Affair in 1985, where the Reagan Administration illegally sold weapons to Iran despite an arms embargo to secure the release of American hostages by Hezbollah and fund right-wing Contra rebel groups in Nicaragua despite Congress prohibiting further funding to the insurgency. In other words, Iran saw the United States as funding both sides of the war without serious reservation.

Beirut Barracks Bombing

The Beirut barracks bombing on October 23, 1983, was one of the deadliest attacks on American forces overseas during peacetime. In the early morning hours, a suicide bomber drove a truck filled with explosives into the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, killing 241 American service members who were stationed there as part of a peacekeeping mission.10 Just moments later, a similar attack targeted a French paratrooper compound, killing 58. The sheer scale and coordination of the bombings shocked the world and horrified the American public. A group calling itself Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility, but U.S. intelligence agencies traced the attack back to Hezbollah. Hezbollah is still active today and operates mostly out of Lebanon. They are an Islamic Shiite terrorist group that has backing, training, and funding from Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps.11 Though Iran denied direct involvement at the time of the Beirut barracks bombing, the evidence pointing to its influence was impossible to ignore.

For Americans, the bombing wasn’t just a horrific act of violence, it marked a turning point in how America viewed Iran’s reach and intentions in the Middle East. This is especially the case today, as this was our first glimpse of how Iran would use various proxy groups to achieve its regional interests. It shifted the tone of U.S.-Iran relations from one of strained diplomacy to something more hardened and confrontational. The attack helped solidify Iran’s image in the American psyche as a state sponsor of terrorism, a perception that would shape decades of foreign policy. In many ways, the fallout from Beirut set the stage for the deep mistrust that still defines the relationship between the two nations today. Iran continues to use and sponsor terrorism to create instability in the Middle East and retain some sense of plausible deniability for kinetic actions that they would not be able to otherwise directly do themselves.

Operation Praying Mantis

Operation Praying Mantis, launched on April 18, 1988, was the largest U.S. naval battle since World War II and a decisive moment in American-Iranian relations. The operation was a direct response to the mining of the USS Samuel B. Roberts in the Persian Gulf by Iranian forces days earlier, which had seriously damaged the ship and injured ten sailors. In retaliation, the U.S. Navy carried out a series of coordinated attacks on Iranian oil platforms and naval vessels.12 By the end of the day, American forces had sunk or disabled several Iranian ships, including the frigate Sahand, and effectively dismantled key elements of Iran’s naval capabilities in the Gulf. The U.S. naval force was so superior to Iran’s that by the end of the operation, Iran had lost roughly half of its regular navy’s combat strength in a matter of hours (wow), which made this one of the most lopsided naval engagements in modern history. Operation Praying Mantis was a massive show of force and sent a clear message to the Iranians that any attacks on American vessels or personnel would come with a steep price. These engagements only further increased the tension between the two nations, and that tension would soon boil over into some costly mistakes on both sides.

Just months after Operation Praying Mantis, a U.S. Navy cruiser, the USS Vincennes, detected what they thought to be an Iranian fighter flying towards their location. Tragically, what was thought to be an Iranian fighter jet was actually Iran Air Flight 655, which was shot down just a few minutes after takeoff, killing all 290 civilians on board.13 The incident occurred in the Persian Gulf, where the Vincennes was operating amid rising tensions and the recent skirmishes with Iranian gunboats. U.S. officials later claimed the crew had misidentified the airliner as an attacking Iranian F-14 fighter jet, and expressed much regret for the incident. The tragedy outraged Iran and shocked the international community. The Iranians saw it as a deliberate act of aggression, although it was most likely a genuine but costly mistake. For many Iranians, the downing of the plane crystallized their perception of the U.S. as a hostile power willing to kill civilians to assert its dominance in the region. Though the U.S. eventually expressed regret and paid compensation to the victims’ families, it never formally apologized, a decision that further fueled long-standing resentment and deepened the already bitter rift between the two nations. Unfortunately, history has a twisted sense of irony in the way horrors can be repeated. Tragically, in 2020, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards shot down a Ukrainian civilian airliner after it took off from Tehran and killed all 176 people on board.14

Trump Pulls Out of JCPOA

If we fast forward a bit, the U.S. government’s main concern with Iran, as far as security interests go (outside of occasional skirmishes with their proxy groups), was the potential of them developing nuclear weapons. For years, the U.S. and its allies worried that Iran was quietly edging toward building a nuclear weapon, with various reports surfacing of Iran having ambitions to enrich enough uranium to construct bombs. After rounds of secret talks and mounting international pressure, negotiations kicked into high gear under President Obama. In 2015, the U.S., along with the UK, France, Germany, Russia, and China, struck a deal with Iran: in exchange for lifting tough economic sanctions, Iran would sharply limit its nuclear program and open it up to international inspections.15 It wasn’t a perfect deal, but for a moment, it felt like diplomacy had worked with a regime that seldom agreed to anything. There was cautious hope that maybe, just maybe, the U.S. and Iran could start pulling back from the decades of mistrust and hostility.

That hope didn’t last. In 2018, President Trump boldly pulled the U.S. out of the agreement, calling it a bad deal that gave Iran too much and got too little in return. Sanctions were reimposed, even harsher than before, and Iran started walking away from its end of the bargain by enriching more uranium and shutting off parts of its program to inspectors.16 The collapse of the deal didn’t just set back arms control efforts, but it also sent U.S.-Iran relations into a downward spiral. Iran felt betrayed, and the U.S. found itself at odds with European allies who still supported the agreement. What could’ve been the beginning of a new chapter turned into yet another reminder of how hard it is for our two countries to find common ground, and the effects of this disagreement are still felt today. (Ask Israel.)

Assassination of Qasem Soleimani

Throughout this timeline, I’ve aimed to give a clear and balanced overview of the major events that have shaped U.S.-Iran relations as we know them today. While it covers what I believe are the most significant turning points, it’s not meant to be exhaustive, and there have been plenty of smaller incidents and developments along the way that also played a role. The goal here is to highlight the key moments that help you develop a broad understanding of the history, especially for those who may not be deeply familiar with the topic. With that being said, the assassination of Qasem Soleimani was one of the most dramatic escalations between the U.S. and Iran in recent memory. On January 3, 2020, the U.S. killed IRGC general Qasem Soleimani by a drone strike near Baghdad’s international airport.17

Soleimani wasn’t just any military figure but the architect of Iran’s regional strategy, overseeing proxy forces across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and beyond through the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. To many in the U.S., he was seen as responsible for the deaths of American troops (which is true) and for orchestrating attacks on U.S. interests in the Middle East. But in Iran, he was viewed as a national hero and symbol of resistance. His assassination sent shockwaves through the region and felt like the closest the two countries had come to open war in decades.

In the immediate aftermath, Iran responded with a ballistic missile strike on U.S. bases in Iraq. The attacks injured over 100 American service members, though, notably, avoiding fatalities. It is believed that Iran intentionally avoided casualties to avoid harsh American retaliation, but to still satisfy the need for some sort of response to the assassination. (A similar scenario played out just recently when the U.S. struck three nuclear sites within Iran, and the retaliatory attack was a missile strike on an American base in Qatar, which resulted in no casualties. This is most likely deliberate.) Soleimani’s death hardened attitudes in Tehran, fueling anti-American sentiment and further entrenching Iran’s commitment to its regional proxy networks. Iran felt as if their national sovereignty was severely violated, while the U.S. felt it had the right to eliminate a threat to American troops in the region. The decision to kill Soleimani was controversial to say the least, and is a transgression in the eyes of the Iranians that probably won’t be forgiven anytime soon.

Present Day

In recent years, Iran has been contributing to the instability within the Middle East mainly through their proxy groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas. The most recent escalation happened on June 13, when Israel launched a surprise preemptive strike on Iran, targeting its nuclear facilities and escalating already tense negotiations between Washington and Tehran.18 Israel’s strikes caused Iran to retaliate by firing countless ballistic missiles into Israel, with some striking Tel-Aviv. After weeks of stalled nuclear talks and ongoing kinetic strikes between Israel and Iran, President Trump ordered a direct U.S. attack on June 21, hitting three major atomic sites overnight. B-2 bombers struck the Fordow and Natanz facilities, while Tomahawk missiles hit the Isfahan center. Trump hailed the operation as a “spectacular military success,” and the Pentagon reported “extremely severe damage” at all three locations, however, the true impact on Iran’s nuclear capabilities remains uncertain.

Iran responded with the aforementioned missile strikes on an American base in Qatar (and laughably awful AI-generated propaganda images on social media), marking a new phase in U.S.-Iran relations. This was the first time the U.S. had carried out direct strikes on Iranian soil, and it also marked the combat debut of America’s so-called “bunker buster” bombs, believed to be the only weapons capable of reaching Iran’s heavily fortified nuclear sites.19 Since the assassination of Soleimani, this was probably the closest the U.S. and Iran have been to open conflict.

Ending Comments

Now that we have reached the present state of U.S.-Iran relations, I hope I have been able to provide you with a broad understanding of some of the key events that have led our two nations to this point. Like most geopolitical issues, the relationship between America and Iran is incredibly complex, and each side views the other as guilty of great sins and differences that are hard to reconcile. The reality is that, as it stands, the Western values that Americans hold dearly are in direct opposition to the strict Shiite Islamic values of the Iranian regime. The regime is regularly responsible for human rights violations against its own citizens and openly supports terrorism in the region. While the U.S. hasn’t always lived up to its ideals, as seen in some of the events covered here, they are still values that we hold and are willing to defend.

That said, while the U.S. will likely continue to oppose regimes that support terrorism or suppress basic freedoms, it’s important to remember that the Iranian government is not the same as the Iranian people. There’s a rich culture and a population that, in many cases, wants something very different from what its leaders enforce. Iran and the U.S. may not share much common ground right now, and maybe that’s necessary in some ways, but I still hold out hope that someday there will be steps toward peace and mutual respect that will earn a place on this timeline, too.

As I briefly touched on at the beginning of this post, many of the earliest Americans, including some of our founding fathers, looked to ancient Persia with admiration. The Persian Empire was seen as a symbol of wisdom, order, and cultural richness. Likewise, the Persians saw the distant Americans as resilient fighters for freedom and liberty, breaking away from British rule and creating a nation for themselves. Even in the early 20th century, American ideals of liberty and self-governance resonated with many Iranians during their own constitutional revolution. For a brief time, both nations looked to each other as examples of what could be achieved through courage and commitment. That shared intellectual and moral curiosity may feel like a distant echo now, but I see it as a powerful reminder that respect and understanding once existed and could, God-willing, someday exist again.

(For a more exhaustive history of American-Iranian relations, I highly recommend the book America and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present by John Ghazvinian.)

For more on Mossadegh. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammad-Mosaddegh

Anglo-Persian Oil Company. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Anglo-Iranian_Oil_Company

1953 Coup. https://www.britannica.com/event/1953-coup-in-Iran

SAVAK. https://apnews.com/article/072580b5f24b4f8ea2402221d530257e

White Revolution. https://www.britannica.com/topic/White-Revolution

Ayatollah Khomeini. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml

1979 Iranian Revolution. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/iranian-revolution-1977-1979/

Iran Hostage Crisis. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/jimmy-carter-and-the-iran-hostage-crisis

Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/81ali.pdf

Beirut Barracks Bombing. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/article/3566652/us-remembers-service-members-killed-in-beirut-bombings-40-years-ago/

Hezbollah. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-hezbollah

Operation Praying Mantis. https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/middle-east/praying-mantis.html

Downing of Iranian plane. https://www.britannica.com/event/Iran-Air-flight-655

Downing of Ukranian plane. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-taken-world-court-over-downing-passenger-plane-2023-07-05/

Iran nuclear deal. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-iran-nuclear-deal

Trump pulls out of Iran nuclear deal. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-ending-united-states-participation-unacceptable-iran-deal/

Assassination of Soleimani. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/us-drone-strike-in-iraq-kills-iranian-military-leader-qasem-soleimani/F914ED1CDB4DD9D0BA53C95F65987743

Israel strikes Iranian nuclear facilities. https://apnews.com/article/iran-explosions-israel-tehran-00234a06e5128a8aceb406b140297299

US bombs Iranian nuclear facilities. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2025/06/22/iran-nuclear-strikes-30000-pound-bunker-busters/84306936007/